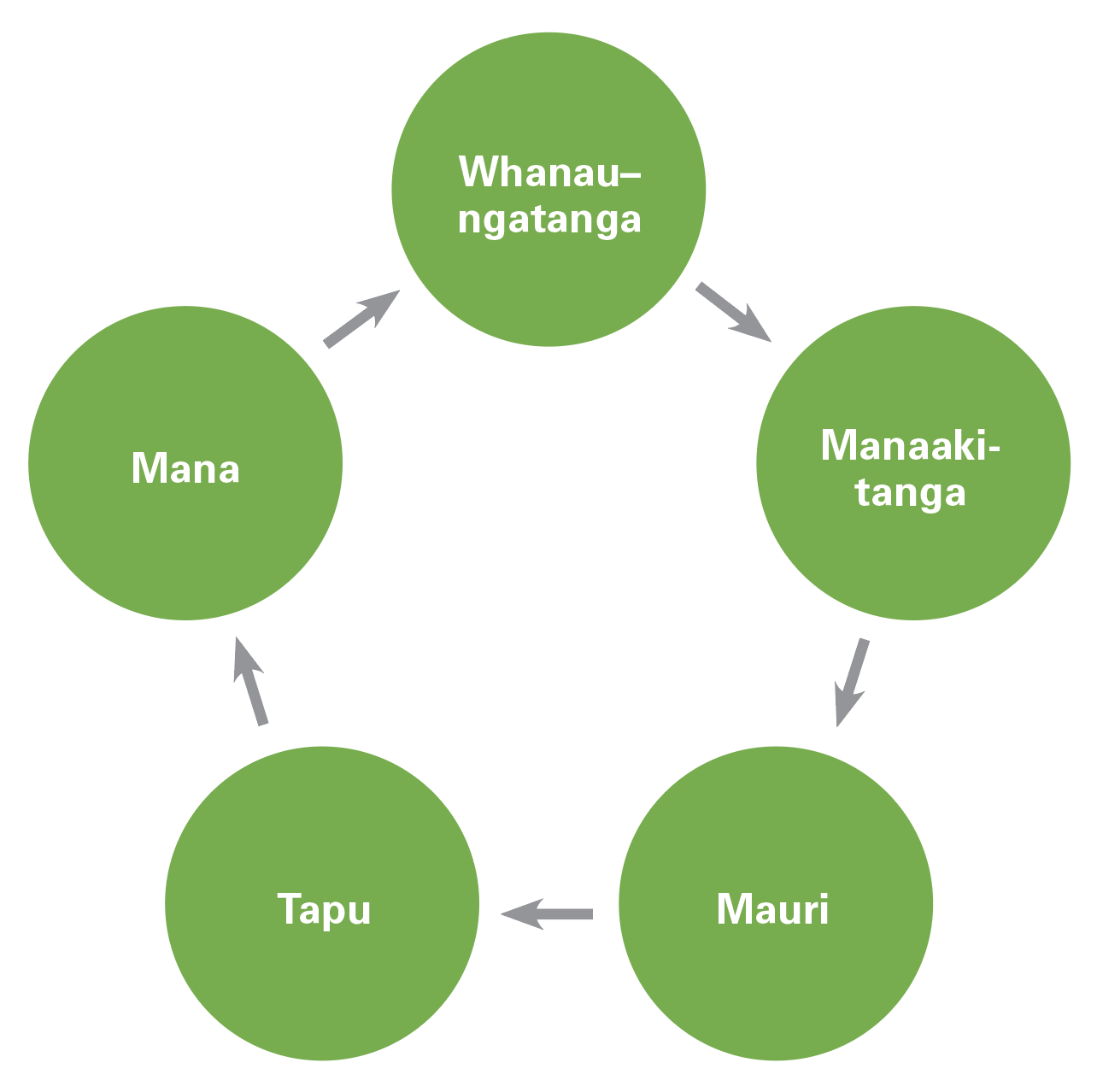

The key issues identified for Māori were for healthcare professionals to consistently provide clear explanations of the purpose and indication (if this is not done, the medicine will not be swallowed), mechanism of action, and two to three key side effects to look out, or be prepared, for.6

Māori generally prefer talking about medicines in a non-clinical environment where they feel more at home, and they feel less emphasis should be placed on high-technology digital resources.6

They feel the mainstream healthcare system doesn’t always meet their needs and that all new New Zealander’s (regardless of origin) should be educated about Te Ao Māori (the Māori world view) and the importance of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.6

Barriers to medicines use are impacted by conflict between the individual, the healthcare professional and the healthcare system. These can be divided into internal factors (psychological, health beliefs, attitudes and/or perceptions of conventional healthcare) and external factors (sociocultural group dynamics, the attitude of the healthcare professional and indifference/ignorance displayed by the healthcare system).

For Māori, concerns about medicines are mostly around efficacy and safety.6 There is a definite grade of scale between the patient’s level of trust of their clinician and their willingness to accept medicines.6,9

Health beliefs

Health beliefs and culturally specific tendencies, including delay in help-seeking behaviour and denial of illness, were particularly apparent.6

Māori seek help in subtle, less overt ways due to their communal style of communication, which can be misconstrued as apathy or lack of interest.6,8,9 Achieving a workable therapeutic partnership, building rapport and gaining trust are of crucial importance, regardless of the ethnicity demographics of that partnership; it is purely about open and honest communication and gaining the patient’s trust.6

Trust

Māori participants were dubious about the efficacy of their medicines, partly due to mistrust of their healthcare professional (particularly hospital staff) and partly due to concerns about drug side effects.6

This finding has subsequently been described as “a long history of mistrust towards Western medicines”. Although the prescription may have been filled, if “medication mechanism of action, origin of medicine, aim of its use, likely side effects and length of treatment” have not been properly discussed, Māori “may still be without the final tools necessary to administer the medicine correctly, or they may feel a lack of trust and collaboration in the process such that they choose not to take the medicine”.9

Māori are often blamed for non-adherence, rather than drilling down to find the failure of the healthcare system to assess and address patient needs correctly in the first place, or why patients are not able to articulate exactly what help they need. One failure is episodic care by different GPs within a practice (ie, lack of consistency), then when presenting to a busy pharmacy dispensing 800–1000 prescriptions daily (ie, tight time frames). This implies that establishing trust and rapport is even less likely than a decade ago. Also, where is the ability to pause for reflection?

It was alright before, when you could go and see the same person, but now every time it’s a different person. They all keep changing.

On the other hand, the community pharmacist may be the only true constant for patients. We must think creatively and carve out small amounts of time to ameliorate disparity and inequity for Māori (even just five minutes). Perhaps individual pharmacists in a joint workplace could each have a dedicated list of patients (eg, by speciality or region).

A 2018 systematic review showed the importance of consistency. Patients seen by the same doctor each time were more likely to follow medical advice, more likely to engage in preventive care more often, and had fewer hospital admissions.14

Cost

Cost was identified as a barrier to adherence for some Māori but not all.6

Both Māori and New Zealand Europeans were suspicious that blister packaging was simply a generator of revenue for pharmacists and of no therapeutic value. Compliance packaging certainly is not a panacea, and some patients are even insulted when offered this because it might imply they have a faulty medicines management system.6

I’ve been prescribed the same pills since 2001, but I couldn’t afford them for three months.

We need to figure out bespoke adherence strategies, rather than just providing generic medicines information.

The debate about the causes and consequences of poverty has moved away from the lack of income of certain ethnic groups to focus on the dynamic social processes that perpetuate a disconnect in society in the world.10,11,15

Of course, poverty in New Zealand can be considered minor when compared with poverty elsewhere. However, the little things matter, such as not getting a supply of medicines at discharge and not being able to afford to fill the written prescription, losing medicines while moving wards in, or leaving, hospital and not being able to afford to replace them, or lack of synchrony of medicines causing endless trips back to the pharmacy, sometimes involving large distances travelled with significant adjunctive petrol costs.10

All of the above are more likely to happen to Māori and Pacific peoples as most are on the bottom of the income ladder. Indigenous peoples are often the most socioeconomically excluded in their own country. Poverty among indigenous peoples is different – it is complex, multigenerational, prevalent and deeply ingrained.15

We should not assume all people have easy access to medicines. We need to “listen to patients’ stories about their difficulties, to try to find ways around these, and to lobby against small (and large) changes in policies that have unintended negative consequences for people living in poverty”.10

This can be linked back to poor governorship (article one). When Māori lost their resources, they lost the power to make their own rules (article two) and govern their own society. Ensuring those living in poverty have a greater participation in their own therapeutic decision-making, allows them the impetus to improve their own living standards and their overall wellbeing.10–13,15

The Health Quality & Safety Commission’s Window 2019 report identified communication as a key issue, stating that Māori respond less positively when asked about their hospital experiences. Māori are less likely to receive diabetes monitoring and early referral for renal dialysis, despite being at higher risk. And even when Māori do engage, this doesn’t always mean decreased inequities. While previous Window reports showed a “closing of the gap” from 2007 to 2015, this has declined over the past five years.12

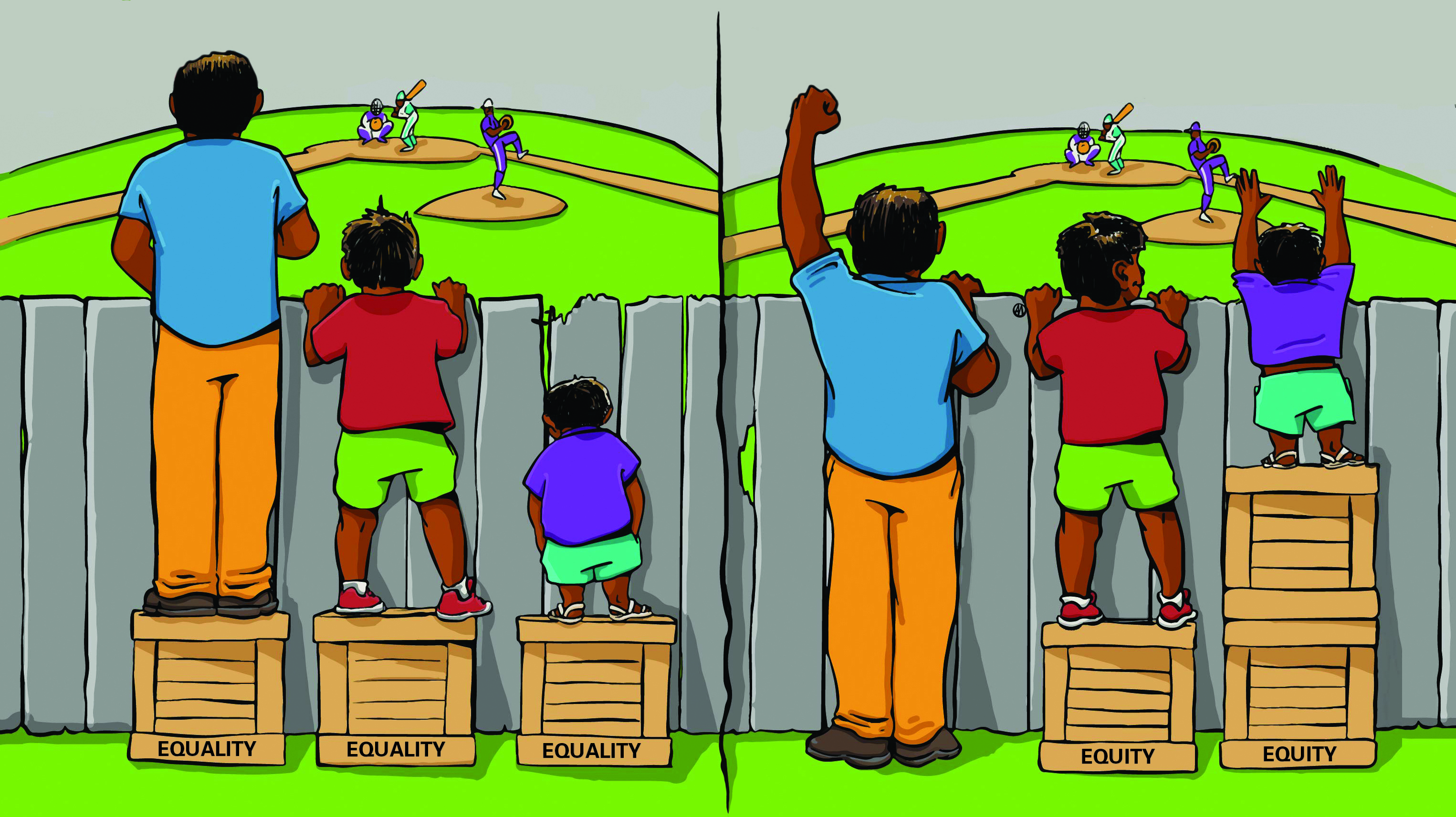

“We should not be trying to eliminate inequity (deficit) but creating equity so that Māori can determine how wellness looks for them”.13 It is more of an attitudinal shift rather than a policies and procedural shift – putting our tangata whenua lenses on, rather like Te Whāriki (the mat), a pre-school education programme that started in kohānga reo and has now been rolled out to mainstream pre-school education in both New Zealand and Australia.

The Pharmacy Today suite of CLASS activities provides meaningful independent and peer group learning that you can put into action, while helping you complete your annual recertification requirements.

The Pharmacy Today suite of CLASS activities provides meaningful independent and peer group learning that you can put into action, while helping you complete your annual recertification requirements.